On Willie Mays, on exuding joy

...and transcending our craft

Noticing statues

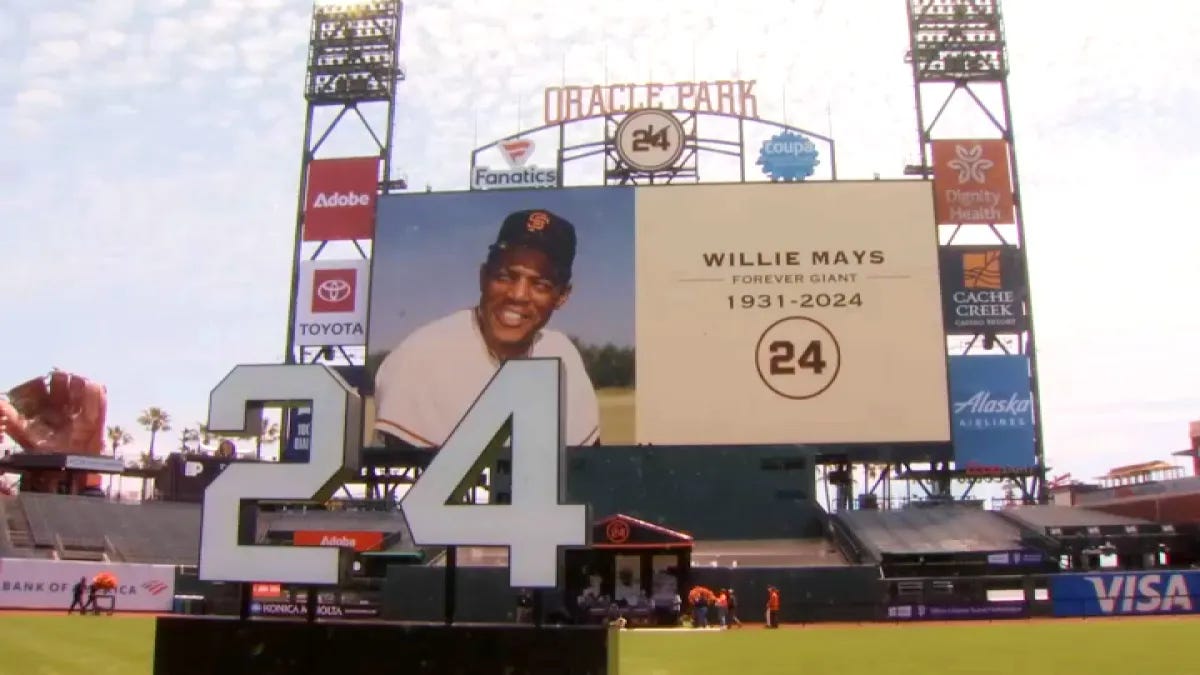

I’d seen the statue of baseball icon Willie Mays, outside (now) Oracle Park in San Francisco, dozens of times.

I wasn’t born into baseball. My Asia upbringing covered athletic pursuits like swimming, badminton, and basketball. As a fan, I was (and still am) crazy about football/soccer.

I’d need a powerhouse baseball team to open me up to its charms. The SF Giants’ three World Series wins in the 2010s made sure of that. It was thrilling to watch the games, and get swept up in the victory parades. As a leadership coach, I nerded out on the management moves that created that winning streak.

But other extracurricular passions, and calendar commitments, kept me from embracing the history of the game, and the lore of its players.

In my lived experience, I’d only seen statues made for people who’d passed. So, I’d long thought the Willie Mays statue had been erected in his memory.

Naming the greats

After grokking this week’s news of Willie Mays’s actual passing, a familiar, soulful, curiosity began to well up inside me. It was the same energy that showed up when music icon Prince transitioned in 2016, an energy that reminded me of my soul’s desire to make music.

I knew I had to follow the energetic breadcrumbs, to learn what Willie Mays’s life had to say to me.

America knows how to celebrate a life well lived, and Willie Mays was no exception. This time, though, even his son Michael suspected his father had picked the date of his passing with strategic precision.

Willie Mays passed on June 18.

The nation marked Juneteenth on June 19, when enslaved people were emancipated in 1865.

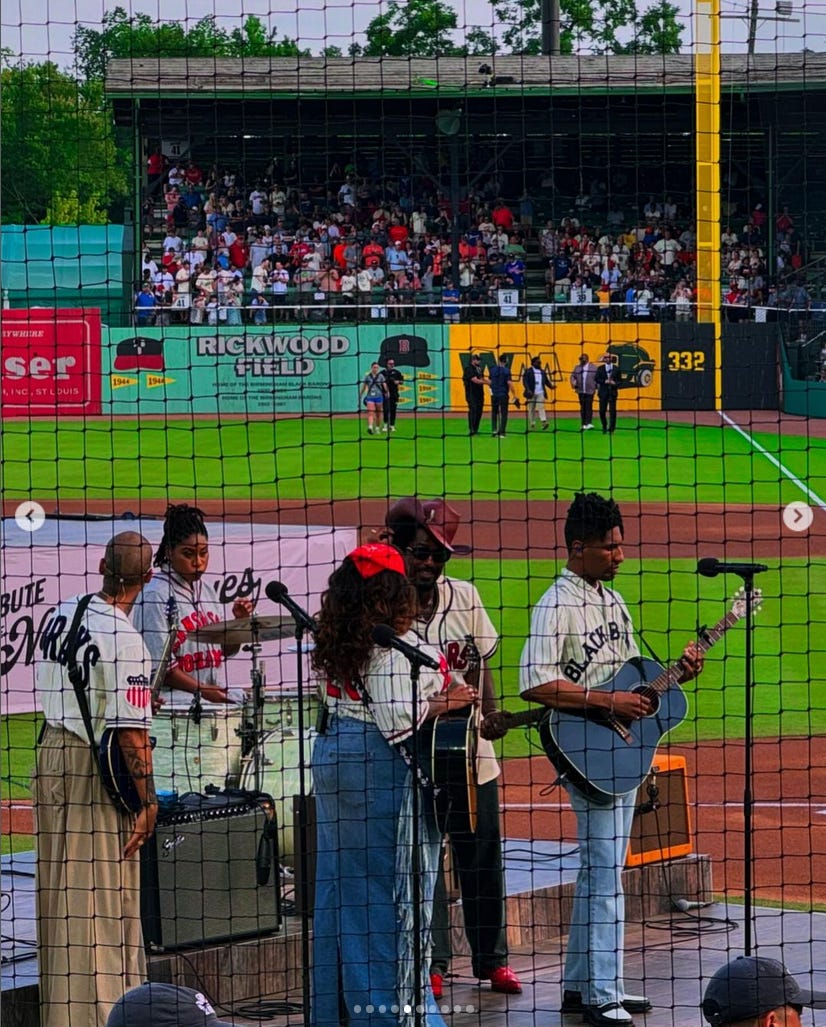

Rickwood Field, America’s oldest existing professional baseball park, hosted a special Major League Baseball (MLB) game on June 20 to honor Negro League greats.

Willie Mays got his professional start at Rickwood Field, and was born just a few miles away from that historic Birmingham, Alabama ball park. All his best baseball buddies, and his biggest fans, would already be gathered there. It would be, and was, the perfect event to celebrate his legacy.

Pioneering a pastime

On June 20, I settled in for a televised night of history and homecoming.

The game opened with a masterfully-curated performance by Jon Batiste.

The teams on the pitch wore throwback baseball uniforms. In mid-game, the broadcast took on a sepia tone and vintage audio. Willie Mays’s Giants jersey number 24 was on the pitch, and on the game clock (locked at 8:24, where 8 was his number with the Negro Leagues Black Barons team).

Fans also gathered for a video feed of the game at San Francisco’s Oracle Park, with its own 24 planted in center field.

I learned about the pain of being a Black baseball player in an age of overt segregation, which mirrored the pain of being a Black musician then. Expected to entertain, subjected to racist treatment.

It could, and nearly did, break the spirit of many a Black baseball great.

But many were also breaking new ground in American culture. Baseball became mainstream when televisions did. Willie, and his subsequent Major League mates, weren’t just becoming fixtures at the ball park. They were also being beamed into living rooms, showcasing their superhuman skills to ever more eager eyes.

Against painful odds, Negro League players had helped turn baseball into America’s national pastime.

Exuding pure joy

Willie Mays played for the love of the game.

He was a consummate showman on the field, and a tireless ambassador outside it. He lived and breathed baseball, publicly promising to watch the broadcast of the Jun 20 Rickwood Field game he’d felt too frail to attend.

In retirement, he’d signed a lifetime contract with the SF Giants, and continued to mentor rising baseball stars. SF residents and baseball fans would hope to meet him, to feel his inspiring energy up close.

In our modern age, where a player is largely measured by, and traded for, their game-play statistics, these stories of Willie Mays refresh and rejuvenate me.

They show me how we can transcend the numbers that drive or define us, how we can remain beloved members of our community till (literally) our dying day, and how our impact can be prematurely immortalized in a statue.

May we all find work we love, and may we also seek to transcend that work, through our joy of being.